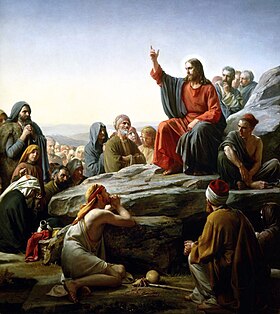

Sermon on the Mount

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

Portals: |

The Sermon on the Mount (anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: Sermo in monte) is a collection of sayings spoken by Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7)[1][2] that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is the first of five discourses in the Gospel and has been one of the most widely quoted sections of the Gospels.[3]

Background and setting

[edit]The Sermon on the Mount is placed relatively early in Matthew's portrayal of Jesus's ministry--following, in chapter 3, his baptism by John and, in chapter 4, his sojourn and temptation in the desert, his call of four disciples, and his early preaching in Galilee.

The five discourses in the Gospel of Matthew are: the Sermon on the Mount (5-7), the discourse on discipleship (10), the discourse of parables (13), the discourse on the community of faith (18), and the discourse on future events (24-25).[4] Also, like all the other "discourses", this one has Matthew's concluding statement (7:28-29) that distinguishes it from the material that follows. For similar statements at the end of the other discourses, see 11:1; 13:53; 19:1; 26:1.

Traditionally, the Mount of Beatitudes has been commemorated by Christians as the physical site at which the sermon took place.[5] Other locations, such as Mount Arbel and the Horns of Hattin, have also been suggested as possibilities.[citation needed]

This sermon is one of the most widely quoted sections of the canonical gospels,[3] including some of the best-known sayings attributed to Jesus, such as the Beatitudes and the commonly recited version of the Lord's Prayer. It also contains what many consider to be the central tenets of Christian discipleship.[3]

The setting for the sermon is given in Matthew 5:1-2. There, Jesus is said to see the crowds, to go up the mountain accompanied by his disciples, to sit down, and to begin his speech.[6] He comes down from the mountain in Matthew 8:1.

Components

[edit]

Although the issues of Matthew's compositional plan for the Sermon on the Mount remain unresolved among scholars, its structural components are clear.[7][8]

Matthew 5:3–12[9] includes the Beatitudes. These describe the character of the people of the Kingdom of Heaven, expressed as "blessings".[10] The Greek word most versions of the Gospel render as "blessed," can also be translated "happy" (Matthew 5:3–12 in Young's Literal Translation[11] for an example). In Matthew, there are eight (or nine) blessings, while in Luke there are four, followed by four woes.[10]

In almost all cases, the phrases used in the Beatitudes are familiar from an Old Testament context, but in the sermon Jesus gives them new meaning.[12] Together, the Beatitudes present a new set of ideals that focus on love and humility rather than force and mastery; they echo the highest ideals of Jesus's teachings on spirituality and compassion.[12]

In Christian teachings, the Works of Mercy, which have corporal and spiritual components, have resonated with the theme of the Beatitude for mercy.[13] These teachings emphasize that these acts of mercy provide both temporal and spiritual benefits.[14]

Matthew 5:13–16[15] presents the metaphors of salt and light. This completes the profile of God's people presented in the beatitudes and acts as the introduction to the next section.

There are two parts in this section, using the terms "salt of the earth" and Light of the World to refer to the disciples – implying their value. Elsewhere, in John 8:12,[16] Jesus applies 'Light of the World' to himself.[17]

Jesus preaches about Hell and what Hell is like: "But I say unto you, That whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment: and whosoever shall say to his brother "Raca (fool)" shall be in danger of the council: but whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire."[18]

The longest section of the Sermon is Matthew 5:17–48,[19] traditionally referred to as "the Antitheses" or "Matthew's Antitheses". In the section, Jesus fulfils and reinterprets the Old Covenant and in particular its Ten Commandments, contrasting with what "you have heard" from others.[20] For example, he advises turning the other cheek, and to love one's enemies, in contrast to taking an eye for an eye. According to most interpretations of Matthew 5:17, 18, 19, and 20, and most Christian views of the Old Covenant, these new interpretations of the Law and Prophets are not opposed to the Old Testament, which was the position of Marcion, but form Jesus's new teachings which bring about salvation, and hence must be adhered to, as emphasized in Matthew 7:24–27[21] towards the end of the sermon.[22]

In Matthew 6, Jesus condemns doing what would normally be "good works" simply for recognition and not from the heart, such as those of alms (6:1–4), prayer (6:5–15), and fasting (6:16–18). The discourse goes on to condemn the superficiality of materialism and calls the disciples not to worry about material needs or fret about the future, but to "seek" God's kingdom first. Within the discourse on ostentation, Matthew presents an example of correct prayer. Luke places this in a different context. The Lord's Prayer (6:9–13) contains parallels to 1 Chronicles 29:10–18.[23][24][25]

The first part of Matthew 7 (Matthew 7:1–6)[26] deals with judging. Jesus condemns those who judge others without first sorting out their own affairs on the matter: "Judge not, that ye be not judged." Jesus concludes the sermon in Matthew 7:17–29[27] by warning against false prophets.

Teachings and theology

[edit]

The teachings of the Sermon on the Mount have been a key element of Christian ethics, and for centuries the sermon has acted as a fundamental recipe for the conduct of the followers of Jesus.[28] Various religious and moral thinkers (e.g. Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi) have admired its message, and it has been one of the main sources of Christian pacifism.[1][29]

In the 5th century, Saint Augustine began his book Our Lord's Sermon on the Mount by stating:

If anyone will piously and soberly consider the sermon which our Lord Jesus Christ spoke on the mount, as we read it in the Gospel according to Matthew, I think that he will find in it, so far as regards the highest morals, a perfect standard of the Christian life.

The last verse of chapter 5 of Matthew (Matthew 5:48)[30] is a focal point of the Sermon that summarizes its teachings by advising the disciples to seek perfection.[31] The Greek word telios used to refer to perfection also implies an end, or destination, advising the disciples to seek the path towards perfection and the Kingdom of God.[31] It teaches that God's children are those who act like God.[32][better source needed]

The teachings of the sermon are often referred to as the "Ethics of the Kingdom": they place a high level of emphasis on "purity of the heart" and embody the basic standard of Christian righteousness.[33]

Theological structure

[edit]The theological structure of the Sermon on the Mount is widely discussed.[7][8][34] One group of theologians ranging from Saint Augustine in the 5th century to Michael Goulder in the 20th century, see the Beatitudes as the central element of the Sermon.[7] Others such as Günther Bornkamm see the Sermon arranged around the Lord's Prayer, while Daniel Patte, closely followed by Ulrich Luz, see a chiastic structure in the sermon.[7][8] Dale Allison and Glen Stassen have proposed a structure based on triads.[8][34][35] Jack Kingsbury and Hans Dieter Betz see the sermon as composed of theological themes, e.g. righteousness or way of life.[7]

Extension

[edit]The Catechism of the Catholic Church suggests that "it is fitting to add [to the Sermon on the Mount] the moral catechesis of the apostolic teachings, such as Romans 12-15, 1 Corinthians 12-13, Colossians 3-4, Ephesians 4-5, etc."[36]

Interpretation

[edit]

A central debate over the sermon is how literally its high ethical standards are meant to be applied to everyday life. Almost all Christian groups have developed non-literal ways to interpret and apply the sermon. North American Biblical scholar Craig S. Keener finds at least 36 different interpretations.[37] Biblical scholar Harvey K. McArthur lists 12 basic schools of thought:[38]

- The Absolutist View interprets the Sermon on the Mount as conveying an unambiguous message regarding moral perfection and enduring persecution. For instance, Anabaptists claim to adhere to a literal interpretation, directly applying the sermon's teachings to their lives.[39]

- Other Christians have addressed the issue by Modifying the Text of the sermon. In antiquity, this modification was sometimes achieved through the alteration of the text itself to render it more acceptable. For example, some early scribes altered Matthew 5:22, changing the phrase "whosoever is angry with his brother shall be in danger of the judgment" to the softened, "whosoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment." Similarly, the phrase "Love your enemies" was changed to "Pray for your enemies," among other revisions.

- The Hyperbole View asserts that certain statements in the sermon are to be understood as exaggerations. A prominent example is Matthew 5:29–30, where believers are commanded to gouge out their eyes and cut off their hands if these body parts lead them to sin. However, there is some debate regarding which parts of the sermon should be interpreted figuratively.[38]

- The General Principles View maintains that Jesus did not provide specific instructions but rather offered broad guidelines for behavior, outlining general principles of conduct.

- The Double Standard View posits that the teachings of the sermon can be divided into general precepts and specific counsels. According to this view, the general precepts apply to the broader population, while the specific counsels are directed toward a select group, typically the pious few. This view reserves a "higher ethic" for clergy, especially those in monastic orders.[40]

- The Two Realms View, associated with the theology of Martin Luther,[41] separates the world into the religious and secular realms. According to this perspective, the sermon applies exclusively to the spiritual realm. In the secular world, individuals' obligations to family, employers, and society may require compromises. For instance, a judge may be compelled to sentence a criminal to death, but inwardly, he should grieve for the criminal's fate.

- The Analogy of Scripture View suggests that the more stringent precepts of the sermon are moderated by other parts of the New Testament. For instance, both the Old and New Testaments hold that all people sin, so the command to "be perfect" cannot be taken literally, and even Jesus himself did not always obey the command to refrain from being angry with one's brother.

- The notion of Attitudes not Acts asserts that, while complete adherence to the Sermon on the Mount is unattainable, the focus should be placed on one's internal attitude rather than external actions.

- The Interim Ethic View holds that Jesus was convinced the world would end imminently, thus rendering material well-being irrelevant. In this view, survival in the world did not matter, as the end times would render earthly concerns obsolete. Although it was known earlier, Albert Schweitzer is particularly associated with popularizing this view.[38]

- The Unconditional Divine Will View, presented by Martin Dibelius, posits that while the ethical teachings of the sermon are absolute and unyielding, the fallen state of the world makes it impossible for humans to fully live according to them. Despite this, humans are still bound to strive towards this ideal, with the realization of the Kingdom of Heaven expected to bring fulfillment of these teachings.

- The Repentance View holds that Jesus knew that the precepts in his sermon were unattainable, and that it was meant to stimulate repentance and faith in the Gospel, which teaches that we are saved not by works of righteousness, but faith in the atoning death and resurrection of Jesus.

- Another Eschatological View is that of modern dispensationalism, first developed by the Plymouth Brethren, which divides human history into a series of ages or dispensations. According to this view, while the teachings of the sermon may be unattainable in the current age, they will become a prerequisite for salvation in the future Millennium (see inaugurated eschatology).[38]

Comparison with the Sermon on the Plain

[edit]While Matthew groups Jesus's teachings into sets of similar material, the same material is scattered when found in Luke.[1] The Sermon on the Mount may be compared with the similar but shorter Sermon on the Plain as recounted by the Gospel of Luke (Luke 6:17–49), which occurs at the same moment in Luke's narrative, and also features Jesus heading up a mountain, but giving the sermon on the way down at a level spot. Some scholars believe that they are the same sermon, while others hold that Jesus frequently preached similar themes in different places.[42]

See also

[edit]- Gospel harmony

- Jesus in Christianity

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You, 1894 Leo Tolstoy book

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c Cross, F.L., ed. (2005), "Sermon on the Mount", The Oxford dictionary of The Christian church, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Baasland, Ernst (2015). Parables and Rhetoric in the Sermon on the Mount: New Approaches to a Classic Text. Tübingen, DE: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161541025.

- ^ a b c Vaught, Carl G. (2001), The Sermon on the mount: a theological investigation, Baylor University Press, ISBN 978-0-918954-76-3. pages xi–xiv.

- ^ The Gospel of Matthew by Craig S. Keener 2009 ISBN 978-0-8028-6498-7 pp. 37–38.

- ^ 'Oxford Archaeological Guide: The Holy Land. 4th edition, 2008. p 279. ISBN 0-19-288013-6

- ^ Although the speeches in Matthew 5-7 and in Luke 6 both begin with beatitudes and end with the parable of the two builders, the settings are interestingly different but involve the same components. Whereas Matthew has Jesus go up the mountain with his disciples, sit, and deliver his speech to the crowds, Luke (6:17) describes him coming down from the mountain with his disciples, standing on a level place, and speaking to the crowds.

- ^ a b c d e Reading the Sermon on the Mount: by Charles H. Talbert 2004 ISBN 1-57003-553-9 pp. 21–26.

- ^ a b c d What are they saying about Matthew's Sermon on the mount?, Warren Carter 1994 ISBN 0-8091-3473-X pp. 35–47.

- ^ Matthew 5:3–12

- ^ a b "Beatitudes." Frank Leslie Cross, Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005 ISBN 978-0-19280290-3

- ^ Matthew 5:3–12

- ^ a b A Dictionary of The Bible, James Hastings 2004 ISBN 1-4102-1730-2 pages 15–19.

- ^ Jesus the Peacemaker, Carol Frances Jegen 1986 ISBN 0-934134-36-7 pages 68–71.

- ^ The Synoptics: Matthew, Mark, Luke, Ján Majerník, Joseph Ponessa, Laurie Watson Manhardt 2005 ISBN 1-931018-31-6, pages 63–68

- ^ Matthew 5:13–16

- ^ John 8:12

- ^ Spear, Charles (2003). Names and Titles of the Lord Jesus Christ. p. 226. ISBN 0-7661-7467-0.

- ^ Matthew 5:22

- ^ Matthew 5:17–48

- ^ See David Flusser, "The Torah in the Sermon on the Mount" (WholeStones.org) and idem, "'It Is Said to the Elders': On the Interpretation of the So-called Antitheses in the Sermon on the Mount" (JerusalemPerspective.com).

- ^ Matthew 7:24–27

- ^ France, R. T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 1118–9. ISBN 978-0-80282501-8.

- ^ 1 Chronicles 29:10–18

- ^ Clontz, T.E. & J., The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh, Cornerstone, 2008, p. 451, ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5

- ^ Stevenson (2004), p. 198.

- ^ Matthew 7:1–6

- ^ Matthew 7:17–29

- ^ The sources of Christian ethics by Servais Pinckaers 1995 ISBN 0-8132-0818-1 page 134

- ^ For Tolstoy, see My Religion, 1885. cf. My Religion on Wikisource.

- ^ Matthew 5:48

- ^ a b Vaught, Carl G. (1986). The Sermon on the Mount: A Theological Interpretation. SUNY Press. pp. 7–10. ISBN 9781438422800.

- ^ Talbert, Charles H. (2010). "Matthew". Paideia: Commentaries on the New Testament. Baker Academic. p. 78. ISBN 9780801031922.

- ^ Christian ethics, issues and insights by Eṃ Stephan 2007 ISBN 81-8069-363-5.

- ^ a b Allison, Dale C. (September 1987). "The Structure of the Sermon on the Mount" (PDF). Journal of Biblical Literature. 106 (3): 423–45. doi:10.2307/3261066. JSTOR 3261066.

- ^ Stassen, Glen H. "The Fourteen Triads of the Sermon on the Mount." Journal of Biblical Literature, 2003.

- ^ Holy See, Catechism of the Catholic Church, section 1971, accessed 30 May 2024

- ^ Keener, Craig S. (2009). "The sermon's message". The Gospel of Matthew. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 160–2. ISBN 978-0-8028-6498-7.

- ^ a b c d McArthur, Harvey K. (1978). Understanding the Sermon on the mount. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313205699.

- ^ "Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO)". first paragraph.

Whereas Luther emphasized salvation by faith and grace alone, the Anabaptists placed emphasis on the obedience of faith.

- ^ Mahoney, Jack (February 2012). "Catholicism Pure and Simple". 2nd, 3rd, and 4th paragraphs.

The most widespread and notorious of these strategies was the double standard approach which developed by the time of the Middle Ages, requiring the sermon to be taken seriously by only some members of the Church.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Cahill, Lisa Sowle (April 1987). "The Ethical Implications of the Sermon on the Mount". Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology. 41 (2): 144–156. doi:10.1177/002096438704100204. S2CID 170623512.

The notion that the Sermon is impossible of fulfillment, but has a pedagogical function, is usually associated with Martin Luther or, as Jeremias puts it, with "Lutheran orthodoxy." However, Luther himself maintained that faith is active in works of love and that it is precisely faith which loving service presupposes and of which it is a sign. For this reason, Jeremias's own hermeneutic of the Sermon carries through Luther's most central insights. The Sermon indicates a way of life which presupposes conversion; the Sermon's portrayals of discipleship, while not literal prescriptions, create ideals and set burdens of proof for all concrete embodiments.

- ^ Ehrman 2004, p. 101

Sources

[edit]- Augustine of Hippo (1885). . Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume VI. Translated by William Findlay. T. & T. Clark in Edinburgh.

- Baxter, Roger (1823). . Meditations For Every Day In The Year. New York: Benziger Brothers. pp. 368–389.

- Betz, Hans Dieter (1985). Essays on the Sermon on the Mount. Philadelphia: Fortress.

- Betz, Hans Dieter (1995). The Sermon on the Mount. Hermeneia. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 9780800660314.

- Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne (1900). . Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Fenlon, John Francis (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Johannes, Peter Van (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Kissinger, Warren S. The Sermon on the Mount: A History of Interpretation and Bibliography. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press, 1975.

- Friedrich Justus Knecht (1910). . A Practical Commentary on Holy Scripture. B. Herder.

- Kodjak, Andrej. A Structural Analysis of the Sermon on the Mount. New York: M. de Gruyter, 1986.

- Lapide, Pinchas. The Sermon on the Mount, Utopia or Program for Action? translated from the German by Arlene Swidler. Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1986.

- Lambrecht, Jan, S.J. The Sermon on the Mount. Michael Glazier: Wilmington, DE, 1985.

- McArthur, Harvey King. Understanding the Sermon on the Mount. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1978.

- Prabhavananda, Swami Sermon on the Mount According to Vedanta 1991 ISBN 0-87481-050-7

- Easwaran Eknath. Original Goodness (on Beatitudes). Nilgiri Press, 1989. ISBN 0-915132-91-5.

- Stassen, Glen H., and David P. Gushee. Kingdom Ethics: Following Jesus in Contemporary Context, InterVarsity Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8308-2668-8.

- Stassen, Glen H. Living the Sermon on the Mount: A Practical Hope for Grace and Deliverance, Jossey-Bass, 2006. ISBN 0-7879-7736-5.

- Stevenson, Kenneth. The Lord's prayer: a text in tradition, Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8006-3650-3.

- Soares de Azevedo, Mateus. Esoterism and Exoterism in the Sermon of the Mount. Sophia journal, Oakton, VA, USA. Vol. 15, Number 1, Summer 2009.

- Soares de Azevedo, Mateus. Christianity and the Perennial Philosophy, World Wisdom, 2006. ISBN 0-941532-69-0.

External links

[edit]- The Sermon on the Mount Site: Extensive range of Sermon on the Mount related resource

- Listen "Blessed are those who mourn" commentary

- The Sermon on the Mount as depicted by Claude Lorrain at the Frick Collection in New York City

- Read Christ Teaching the Beatitudes in the Americas in The Book of Mormon